Download Market Mechanisms in Sub-Central Public Service Provision: A Comparative Analysis and more Study notes Nursing in PDF only on Docsity!

OECD Working Papers on Fiscal Federalism No. 06

Market mechanisms

in public service provision

Hansjörg Blöchliger

https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/4c56c441-en

OECD Network on Fiscal Relations Across Levels of Government

MARKET MECHANISMS IN PUBLIC SERVICE PROVISION

Hansjörg Blöchliger, Economics Department, O.E.C.D.

MARKET MECHANISMS IN SUB-CENTRAL PUBLIC SERVICE PROVISION

1. Introduction and main findings

- This paper compares and analyses the use of market mechanisms in core sub-central policy areas, namely education, health care, transport, social protection, and environment. Arrangements like tendering, outsourcing, user choice and competition, user fees and performance-related funding can help to improve quality of service provision or lower its cost. With around 32% of total public expenditure and often wide-ranging spending powers, sub-central governments (SCG) have considerable leeway for improving their services by relying on market mechanisms. The decentralised and often fragmented nature of sub-central government poses some special challenges to efficient arrangements, however, and may require central government support or stronger inter-jurisdictional co-operation. And while market mechanisms are being harnessed ever more broadly, limits to a more extensive use have become apparent, particularly in the potential trade-off between greater efficiency and equity objectives, or between efficiency and sub-central accountability.

- The paper is organised as follows. This section gives the main findings and draws some policy implications. The second section describes the properties of “market mechanisms”, develops a framework of institutional indicators for measuring their use, and presents the public services selected for the market mechanism test. The third to fifth sections describe, for the various market mechanisms under study, both the policy issues involved and the extent to which sub-central governments rely on those mechanisms, as portrayed by a set of institutional indicators. The sixth section presents a comparative summary indicator portraying the use of market arrangements in OECD countries and the policy reform gap for the selected sub-central services. The seventh section deals with potential trade-offs and side effects on equity and sub-central accountability.

- The main findings can be summarised as follows:

- Sub-central governments are sometimes hesitant to apply market mechanisms : SCGs make use of market-like arrangements to a varying extent and for most services, regulatory innovations like private provision, competitive tendering and user choice have become more common than financial innovations like user fees and voucher-like funding arrangements.

- Sub-central technical services are closer to the market than social services : In technical services like public transport or waste collection market arrangements such as tendering, competition or user fee funding are quite advanced. In social services like education, health, or childcare market arrangements such as user choice, private provision or performance- related funding is less common.

- Sub-central out-contracting is hampered by a fragmented regulatory framework. Tendering, outsourcing and public-private partnerships have become quite common at the sub-central level, particularly for technical services. However, efficiency of outcomes is sometimes reduced by non-harmonised regulation across levels of government and the absence of inter- jurisdictional co-ordination.

- User choice is often limited : Sub-central governments considerably restrict user choice in compulsory education and a little less for hospitals, childcare and nursing homes. Giving more choice to consumers can increase providers’ responsiveness but may require the setup of inter-governmental funding arrangements.

- Sub-central governments rely little on user fees and performance-related funding: Most user fees accrue to the sub-central level, but usually cover only a small part of total cost. Also performance-related funding – like vouchers and other use-based funding – is not very frequent. Enhancing their use may also require intergovernmental funding arrangements.

- Equity is an important concern : Market mechanisms may jeopardise equal and universal access to public services. To promote equal access, most governments have put minimum standards in place, but also measures like service obligations, means-tested income support, user fee differentiation, voucher systems or specific grants to providers.

- Central regulation may reduce sub-central autonomy. Central regulation on market mechanism implementation or on service standards can reduce sub-central service accountability. Framework legislation -- leaving SCGs more room for flexible adaptation -- and fiscal equalisation -- which allows but does not compel SCGs to reach national standards -- can reduce this trade-off.

- The analysis shows that there is a substantial scope for increasing the efficiency of public service delivery through market mechanisms, but also suggests important impediments in doing so. The main policy implications, for both central and sub-central governments, are described in Box 1.

Box 1. Conclusions and policy options

Relying on policy evaluation and indicators portraying their current use, the paper shows how and where market mechanisms could increase efficiency of public service delivery, suggesting the following policy options for both central and sub-central government:

- Contracting out : by relying more on open tenders, governments are likely to obtain public service delivery at lower cost. In order to avoid fragmented markets detrimental to efficiency, tendering rules should be harmonised across jurisdictions and government levels and central or sub-central governments may set up specialised agencies to deal with contracting out.

- Granting user choice : user choice is likely to increase responsiveness of service providers. Mechanisms whereby money follows the user (“vouchers”) can strengthen this effect. To be viable across jurisdictions, user choice and voucher systems must be introduced together with horizontal financial agreements or central government compensation.

- Relying more strongly on user fees : user fees may accommodate excessive demand as well as raise revenue in order to increase public service quality. User fees should be closely related to public service cost, in order not to become a form of hidden taxation.

- Promoting equal access : increasing the use of market mechanism can -- but need not -- have undesirable distributional effects, both in social or geographical terms. Both central and sub-central government may have to introduce explicit minimum standards regarding service coverage, introduce means-tested income support or grant subsidies to service providers. Governments may also have to ensure that providers are not allowed to turn users away.

- Maintaining sub-central autonomy: centrally-established rules may have to ensure efficient implementation of market mechanisms. To reduce the trade-off between central regulation and sub-central service accountability, central government may enact framework legislation, leaving more flexibility to SCGs. Also fiscal equalisation can help SCGs reach national standards but does not compel them to do so.

them to the institutional indicators and help identify those arrangements most likely to promote efficiency.^1

- The indicator set is shown as an “indicator tree” with low-level indicators (LLI), intermediate indicators (ILI) and the summary indicator (SI) (Figure 1). Indicator values draw on responses to the 2007 Network questionnaire. Indicator construction starts with a series of 15 LLIs that describe one specific market mechanism aspect. Indicator values are scaled between 0 and 10, with a higher value associated with a more favourable arrangement. LLIs are then aggregated to form three ILIs reflecting the three market mechanism groups -- (a) private provision and contracting out, (b) user choice and competition, (c) price signals in funding -- described above. The three ILIs are finally aggregated to yield a single summary indicator portraying the use of market arrangements in public service provision. Indicator selection and results will be presented in more detail in the appropriate sections. Details on coding and aggregation across services, SCG levels and indicators, in order to obtain the summary indicator, are explained in the Annex.

- Particular weight is given to the consistency of market arrangements. The policy background for doing so is that market mechanisms are supposed to be more efficient if applied as a coordinated package rather than as isolated measures. Consistency is accounted for in several ways: first, by inserting specific “consistency indicators”, second, by applying the random weights technique when aggregating indicators, and, third, by applying both additive and multiplicative aggregation to intermediate indicators in order to obtain the summary indicator. Consistency across services is however not assessed, assuming that low or inefficient implementation of market mechanisms in one service ( e.g. public transport) does not affect the efficiency outcome in another ( e.g. nursing homes). A more detailed description of the procedures to reflect consistency is provided in the Annex.

[Figure 1. Market mechanisms in public service provision: indicator tree]

2.3. Services selected

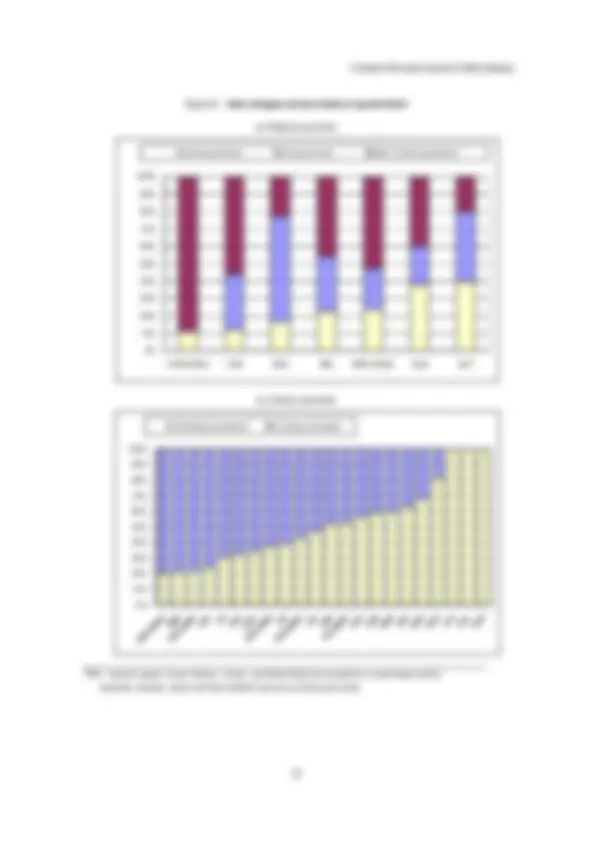

- When selecting public services for the market mechanism test, it is useful to recap on the level, evolution and functional division of SCG expenditure. Sub-central governments account for 32% of total government expenditure on average, with the share having increased by 3 percentage points in the past ten years (Figures 2 and 3). Cross-country variation is, however, large. In more than two thirds of countries the sub-central spending share rose. In almost every country for which data for two sub-central levels are available both the local and the state level moved in parallel.

[Figure 2. Decentralisation of public spending, 2005]

[Figure 3. Decentralisation of public spending, evolution 1995-2005]

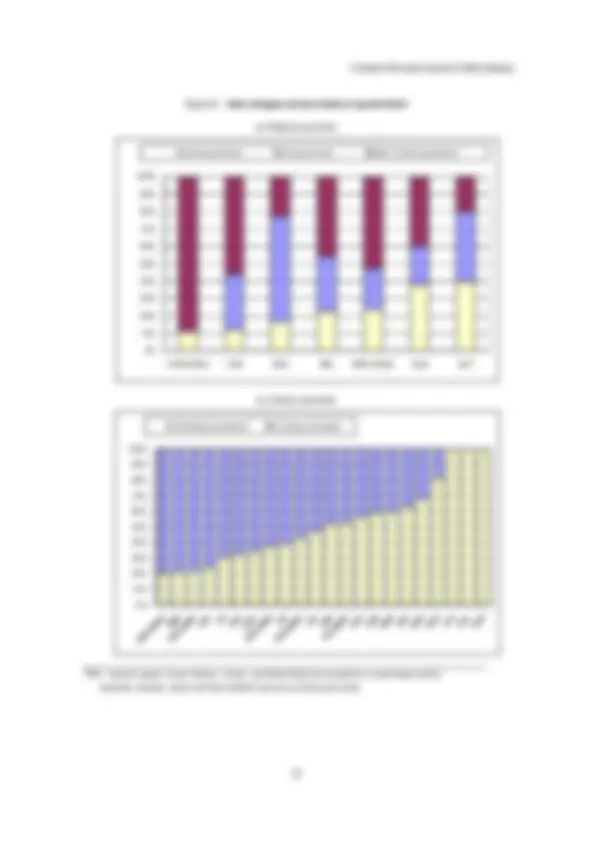

- Figure 4, which is divided into a section for federal/regional countries and unitary countries, shows the main policy areas on which SCGs spend money (for a closer analysis see Table A4 in the Annex)^2. Accounting for around a quarter of SCG expenditure, education is by far the most important item, followed by social security and welfare, economic affairs, health care, and finally environmental protection. The “other” category which plays a more important role in federal than in unitary countries includes different neighbourhood services such as culture, sports and recreation. Again cross-country variation in spending assignment is large, but in most countries education, economic

- Such empirical analysis was performed for primary and secondary education, where a set of institutional indicators in the education sectors was regressed on educational outcomes drawn from the PISA studies (Sutherland and Price, 2007) (^2). Policy areas are classified according to the National Accounts Classification of Functions of Government

(COFOG-1).

affairs, health care, social protection and environment put together make up roughly 65 to 75% of total SCG spending.

[Figure 4. Sub-central spending by functions]

- Based on Figure 4, Delegates of the Statistical Working Group meeting in February 2008 selected a set of sub-central services for the market mechanism test (Table 1). Those services embrace a wide spectrum of sub-central policy areas and are thought to constitute major sub-central expenditure items.^3 A number of traditional SCG services where market mechanisms are widely applied were left out, e.g. network industries such as electricity or water provision. This might be unfortunate but can be justified since the objective of this activity is to analyse services for which public spending is significant.^4 Actually, if all market mechanisms were applied to a public service, the latter would disappear from the government financial accounts.

[Table 1. Public services covered]

3. Private provision and contracting out

- This section deals with the first branch of the market mechanism indicator tree shown in Figure 1. It first deals with policy issues related to private provision, tendering, outsourcing and public-private-partnerships in the provision of public services and then presents the results of the institutional indicators measuring the extent to which countries rely on private providers and contracting arrangements when providing services.

3.1. Private provision

- Private provision means service production by companies, cooperatives, foundations, consumer associations and other non-governmental organisations. Most meta-studies evaluating SCG services acknowledge that privatisation increases productivity, although they often mention that the effect is stronger in the short than in the long run and that competition among providers is a much stronger drive than private provision itself ( e.g. for technical services Jensen and Stonecash, 2004). The productivity gains from private provision are likely to root in more flexible production processes. Private providers tend to operate under less rigid organisational rules, to have more flexible labour relations, to be more innovative and are more likely to adapt services to consumer demand (Farsi and Filippini 2004). In order to avoid that profit-seeking can mitigate the search for better quality or lower cost -- particularly if competition among providers is limited -- many SCGs permit market access to private non-profit organisations only.

- All countries rely at least partly on private providers when supplying public services (Table 2). Australia, the Netherlands and Belgium do so more than Turkey, Greece or the Slovak Republic. Private provision is more common in technical services such as public transport and waste collection than in social services such as hospitals, childcare and nursing homes where principal-agent problems -- such as the definition and supervision of quality standards -- may arise. Although primary and secondary education is the largest single sub-central budget item, here private provision plays little or no role at all; moreover in some countries private schools cannot obtain any funding from government. Tertiary education is more varied, with many private providers offering university and

- Expenditure data at the service level (COFOG-2) are however not yet available The COFOG- classification covers around 60 to 70 services. COFOG-2 is in a preliminary stage and currently tested by a European Union task force.

- Sweden stated that it did not fill in the questionnaire for “waste collection and disposal” as this service was almost entirely fee-funded and representing a tiny portion of SCG expenditure only.

Box 2. Private provision and contracting out in public transport: a snapshot of OECD countries

Starting in the mid-’90s, OECD countries have considerably reformed the regulatory framework in local and regional public transportation services. Transport companies were privatised, tendering became common, and markets were opened to new providers, resulting in productivity gains and improvements in service levels. Most countries have different regulatory frameworks for local/regional and for national public transport services, and the market for local and regional transport services today is in many countries more open to competitive forces than national, long-distance public transport, often provided by a monopolistic state-run railway company.

Market openness is most advanced in inter-regional bus transport. Bus companies often work on a commercial basis, are free to enter the market and to offer whichever scheduled service they deem profitable, but usually need a concession. Bus services in sparsely populated areas are in general tendered, with the winning bid going to the company asking for the lowest subsidy to run the service (reverse bidding). In large metropolitan areas transport services are usually overseen by a public transport authority organising the different transport modes (trains, metros, trams, buses) and acting as a one-stop-shop for users. Here tendering is less common and services are often provided by a public company, with bus services more open to the market than railways. Some private or sub-centrally government-owned railway companies operate on their own tracks or on the network of a national provider, but private providers offering intra-urban or suburban rail services on an open access basis remain the exception rather than the rule. In middle-sized cities where transport networks are less complex, where externalities between national and sub-national network utilization are smaller and where transport relies largely on buses, tendering has become quite frequent. In most cases, tenders are offered for entire networks rather than single lines, and the tendering period is for 5 to 8 years.

Regulatory reforms in sub-central public transport services have not advanced evenly, however. Around half of OECD countries require sub-central governments to open sub-central public transport services to competition, generally in the form of tendering. The European Union exerts some pressure through their internal market programme but sector-specific legislation has not yet passed. Many countries are still in a transition period where some jurisdictions have opened their markets while others have not or for parts of their networks only. Moreover, sub-central governments where transport services are produced “in-house”, i.e. through a government agency instead of an autonomous (public or private) company, are not required to tender. Tendering rules are often skewed towards public providers ( e.g. private firms have to pay taxes while public agencies do not), and only a few countries require strict policy neutrality between private and public providers. Inter-regional bus services are severely restricted or forbidden outright in many countries in order to shelter railway companies from competition.

Further reforms of the sub-central public transport regulatory framework concentrate on metropolitan areas where competitive tendering is slowly becoming more common. Also, railway reforms can open up one of the backbones of metropolitan public transport and reduce the gap between a highly restricted rail sector and a more open bus sector. Applying uniform market arrangements across jurisdictions, levels of government and transport modes could allow for more coherent and efficient public transport networks.

Source: Questionnaire responses provided by Finland, the Netherlands, Italy, Japan, Sweden, Switzerland; OECD, 2006 and OECD, 2007.

- Outsourcing : Outsourcing is the transfer of support functions to an external organisation. Outsourcing is different from tendering since the core service -- such as teaching in a school or medical care in hospitals -- remains within the public provider, but outsourcing procedures are otherwise quite similar to tendering. According to questionnaire responses, support functions typically outsourced include cleaning, security, catering (schools, hospitals, nursing homes, childcare), maintenance (transport, waste collection), and in some cases IT services. Taking all government levels and functions together, outsourcing accounts for 10 to 20% of value added, with education and health care located at the lower end (Lundsgaard, 2002). In general sub-central governments are free to decide what functions to outsource, except for core functions in education and health care where central government often sets limits.

Public-Private Partnerships : The term Public-Private Partnerships (PPP) embraces infrastructure projects whose design, funding, construction and, sometimes, operation is conferred to a private provider. In turn, the private provider receives an annual subsidy for a fixed time. PPPs have become popular since they not only tend to increase allocative efficiency but allow sub-central governments to spread spending more evenly over an investment’s life span. Most PPPs are contracted at the sub-central level. In Germany, around 80% of PPP-investment is spent at the Länder and municipal level, making up 2 to 3% of SCG investment (Deutsches Institut für Urbanistik, 2005), while in France, more than 50% of PPPs are arranged at the sub-central level (Institut de la Gestion Déléguée, 2006). With the “Private Finance Initiative” the United Kingdom has the most advanced PPPs covering around 200 projects totalling £26 billion and representing 10 to 15% of total public service investment, mostly administered by local governments (UK Treasury, 2007).

- Sub-central governments have to weigh the advantages of contracting out against some pitfalls.^7 SCGs often find it difficult to specify contracts, to assess the risks associated with long-term projects and to distribute them fairly between the private and the public sector. Contractual agreements can unduly play in favour of the private sector as sub-central jurisdictions negotiate with experienced private contractors, often operating internationally. While some central governments have set up specialised agencies to deal with private sector involvement in out-contracting projects (Australia, Ireland, the United Kingdom), sub-central governments have less access to specialised knowledge. Stronger inter-municipal cooperation and information exchange could reduce asymmetries and build up the capacities to deal with privately financed projects. Moreover, some funding arrangements -- PPPs in particular -- shift financial obligations to the future and may serve to bypass self-established or central-government-imposed fiscal rules (Sutherland, et al., 2005). Out- contracting may also reduce sub-central budget accountability, particularly if it is financed through off-budget operations.

- Jurisdictional fragmentation is a salient obstacle, for both governments and providers, to achieving satisfactory contracting results, particularly for network services. In many countries, individual jurisdictions are too small to allow providers to reach sufficient economies of scale and specialisation, and varying contracting rules and timings make it hard for operators to offer optimal network sizes across jurisdictional borders. Since sub-central governments sometimes prefer “their” local incumbent over an outside provider, there are often as many different operators as there are jurisdictions. Constrained by jurisdictional fragmentation, Italian local and regional bus services appear to run below optimal density (Cambrini and Filippini, 2003), and most Swiss utilities such as railways or electricity distributors are clearly undersized (Waldmann, 2003).^8 Harmonising tendering rules across jurisdictions and government levels can help overcome those inefficiencies, and intergovernmental co-operation may allow a build up of specialised knowledge in contracting. In European countries sub-central tendering is increasingly subject to EU internal market regulations trying to enforce uniform tendering rules.

3.3. Results for the intermediate institutional indicator “private provision and contracting out”

- As described in earlier sections of this paper, the use of market mechanisms in public service provision will be measured using a set of institutional indicators. The extent to which SCGs

- An assessment of the pros and cons of PPPs at both the central and sub-central level in Germany can be found in OECD (2006). For the United Kingdom, Shaoul (2005) and Allen (2001). (^8). Jurisdictions may also be too large for a single network and a division into several networks may be more

efficient. Some large cities tender bus services along urban districts and even on a line-by-line basis (Toner, 2002), although empirical evidence suggests that network services should be tendered as such ( e.g. Karlaftis and MacCarthy, 2002).

[Table 3. User choice for sub-central services]

- User choice varies greatly across countries but less so across services (Table 4). Australia and Denmark grant free user choice to the services analysed in this document, while choice is quite restricted in Finland and in Switzerland. User choice is quite common in childcare and the hospital sector although for the latter may depend on whether or not a treatment can be obtained in an assigned hospital.^11 User choice is most restricted in primary and secondary education, reflecting the traditional system where parents are assigned a school where they reside. In some countries users have free choice within their own jurisdiction -- municipalities, counties, school districts -- giving them limited choice, but are not allowed to select a provider in a neighbouring jurisdiction. In all countries users are free to choose between public and private providers (not shown in the table), although actual choice may be limited as in some countries private providers receive no government funding and hence have to levy fees.

- User choice across jurisdictions brings with it some externality problems. If users have a choice, jurisdictions may be tempted to reduce their own service responsibilities and shift them onto others. Such inter-jurisdictional manoeuvrings may either result in a long-term under-provision of sub-central services, or lead to an excessive fiscal burden for jurisdictions that continue to cater for non-residents. User choice arrangements may even break down as jurisdictions have little incentive to accept users from neighbouring jurisdiction without proper compensation schemes.^12 To ensure that user choice is beneficial for consumers and viable for all jurisdictions, SCGs may have to set up intergovernmental financial arrangements that take cross-border service use into account. Switzerland has designed a horizontal arrangement in vocational tertiary education that combines free school choice with a compensation for non-resident students, giving incentives for vocational schools to attract outside students (OECD, 2003). Denmark provides a voucher-like system for childcare allowing parents to use an institution outside their municipality of residence (questionnaire response).

4.2. Market access and competition among providers

- Market access is an obvious complement to user choice. The welfare-promoting properties of user choice are much enhanced if they are matched by providers’ rights to enter the market and compete for customers. In the countries and for the services under scrutiny here, private providers have the potential right to enter the market (see the section on private provision). However, free entry is sometimes limited by tendering, particularly in the technical services such as transport or waste collection. In the “social” services, actual competition between public and private providers may be distorted if SCGs provide little or no public funding for private providers, forcing them to levy user fees. More balanced funding arrangements can give users more choice, but those arrangements have to ensure that service demand may not reach financially unsustainable levels.

- SCGs have a tendency towards service regulation that prevents private agents from entering the market (Joumard et al ., 2003). Regulation can be particularly restrictive in some social services. The rules to open a hospital are sometimes so strong that private providers are almost entirely

in turn is one of the main criteria for parents to choose their place of residence. Choice of residence is an indirect form of user choice. "Direct" and “indirect” user choice may hence be substitutes to some extent, leading to similar efficiency results through two different channels.

- In Denmark and the United Kingdom patients are allowed to choose a hospital only if the assigned hospital is not able to provide the required treatment within a certain delay (information from questionnaire responses).

- Norwegian municipalities, responsible for a large number of social services, tended to shift responsibilities for schools and elderly care to neighbouring jurisdictions (OECD, 2002). US and Swiss central cities often provide services to the wider suburban area without being compensated (OECD, 2002).

excluded from the general hospital sector.^13 In some countries, opening a nursery requires high professional qualifications and administrative requirements to discourage flexible parental and neighbourhood self-organisation ( e.g. Filippini and Iten, 2005). Moreover, a regulatory framework that differs across jurisdictions fragments the market and thereby reduces economies of scale and scope and discourages competition across SCG borders. While some services do indeed require careful government regulation, neighbourhood services where output is easy to monitor should be regulated in as simply a fashion as possible.

4.3. Results for the intermediate indicator “user choice and competition among providers”

- The extent to which SCGs grant individual user choice and market access for private providers is measured by institutional indicator 2 “user choice and competition among providers”. This intermediate indicator is based on five low-level indicators (LLIs): LLI-6 measures whether users have choice within their jurisdiction of residence, LLI-7 measures whether users have choice across jurisdictional borders, LLI-8 measures the extent to which private service providers have access to the market, LLI-9 whether SCGs grant both user choice and market access for service providers, and LLI-10 assesses central government’s role in granting user choice and market access at the sub-central level. All information contained in the LLIs is described in the policy parts of this section. Coding for LLIs to obtain the intermediate indicator is shown in Table A1 in the Annex.

- Numerical results for the intermediate indicator 2 display high values for Denmark, Australia and Belgium (Walloon part), and low values for Turkey, Norway, and Austria (Figure 9). User choice arrangements are particularly consistent in Denmark while there is some dispersion in Norway or Sweden. Averages for ILI-2 are higher than for ILI-1, suggesting that user choice is more developed than private provision and tendering. With a few exceptions, the within-country confidence intervals are relatively small, pointing at consistent user choice and competition arrangements.

[Figure 6. Intermediate level indicator 2: user choice and competition]

5. Price signals in funding

- This section deals with the third branch of the market mechanism indicator tree shown in Figure 1 “price signals in funding”. The policy issues related to user fees and use-related funding mechanisms are first discussed and the section then presents the institutional indicator results measuring the extent to which SCGs use price signals when funding their services.

5.1. User fees

- User fees cover all individual payments to public service providers, including collective, private co-payments through insurance schemes, in return for services provided. User fees can be beneficial both for containing excessive demand for and for fostering supply of public services. Since many sub-central services are well suited for individual pricing, user fees have become an important SCG revenue source. According to the questionnaire, user fees cover a significant part of cost in sub- central services like public transport and waste collection but less so in services like tertiary education, nursing homes and childcare. No user fees are generally levied in primary and secondary education. An overview on the level and intergovernmental composition of user fees in OECD countries is given in Figures 7 and 8, although these numbers must be handled with care (see Box 3).

[Figure 7. User charges in OECD countries]

- This could be the case in the Netherlands where hospital care is almost entirely provided by non-govern- mental foundations. Although the market for hospitals is potentially open, new providers hardly come up, and private for-profit care is restricted to a few specialised clinics (information provided by questionnaire).

schemes to cope with the externalities of private transport.^16 If properly designed and reflecting both service demand and environmental impact, user fees may become the pivot of SCG ecological tax reform.

- User fees can also raise revenue to relieve infrastructure bottlenecks or improve service quality. Financial constraints have prevented urban transport systems from coping with growing demand, which has led to considerable congestion and productivity losses (OECD, 2002). In most countries, user fees cover 50% or less of urban public transport cost, depriving transport investment funds from sufficient revenue. As the price elasticity of urban transport is very low (Victoria Transport Policy Institute, 2007), higher ticket prices is a way of generating resources for new transport infrastructure. In tertiary education, higher tuition fees can help fund additional investment in teaching capacities and quality and ease supply constraints (Oliveira-Martins, 2007). Although higher tuition fees could potentially reduce demand, some country experience suggests that combining user fees and measures targeted at poorer students actually increases enrolment.^17 As fees should be used for the services for which they are levied, their revenue should remain with providers -- transport companies, universities etc. -- or be earmarked for investments in those services if they enter general government accounts.

Box 4. Differentiating user fees between residents and non-residents

According to questionnaire responses, only in a few countries are jurisdictions allowed to differentiate the level of user fees between residents and non-residents. They do so particularly in cases where services are financed through sub-central taxes, and they justify price differentiation on the grounds that non-residents do not pay taxes to cover service cost. While price differentiation at first sight erects barriers against the free flow of people, it can be seen as a means for demand management and for generating additional resources, and it enhances a jurisdiction’s scope for negotiating horizontal financial arrangements. Price differentiation between residents and non-residents can hence reduce free-riding and allow recovering a part of service cost, either through individual or through collective payment arrangements. The potential to differentiate prices reduces incentives for an individual SCG to shift service responsibility onto other jurisdictions and opens the way for a more balanced division of spending across jurisdictions.

Source : questionnaire responses

- Fiscal considerations, service characteristics and the wider administrative environment impose constraints against stronger reliance on user fees. In many countries, SCGs have an incentive to levy user fees instead of taxes for fiscal reasons, so regulation may require that fees be introduced on a strict cost-recovery basis only.^18 Many sub-central services are monopolistic in nature, and the decision on level and structure of user fees should be allocated to government rather than providers. For some services such as health care, where consumers are unsure about actual needs and where user fees could induce a spiral of supply-induced demand, SCG may have to set limits on the right of providers to define user fee levels. More generally, some country evidence suggests that user fees are best applied in a framework where providers are competing with each other, where SCG budgets report service revenues and costs in a transparent way and where citizens have some control over fees (Groot and Budding, 2004).

(^16). London in 2003 introduced an ambitious congestion pricing scheme aiming not primarily at raising

revenue but at containing congestion and negative environmental impact (Leape, 2006). (^17). The introduction of fees and income-contingent student loans in Australia and New Zealand was met

with an increase of enrolments by 50% and 90% respectively (OECD, 2007b, US Survey). (^18). Many fiscal equalisation arrangements do not include user fees into the sub-central revenue base, so SCG

have some incentives to replace taxes by fees (Groot and Budding, 2004).

5.2. Vouchers and other use-related funding

- Vouchers and other “money follows the user” arrangements link public subsidies to service demand. Such arrangements are intended both to increase providers’ responsiveness to consumer tastes and preferences and to contain service cost. While “pure” voucher systems where consumers receive a lump sum from government are still unknown, use-related funding where government pays providers according to a use indicator is becoming more common. Examples include schools funded according to the number of pupils or nursing homes funded by the number of residents. Voucher-like subsidies are often risk- or cost-adjusted, e.g. by weighing per-student payments with a need factor or the cost of a curriculum. The funding of hospitals based on diagnosis-related groups is currently the most sophisticated funding system. Use-related funding varies across countries, but “full capitation” whereby the number of users entirely defines the amount reimbursed to a provider is still the exception (Table 4). User-related funding is applied less often in public transport and waste collection, partly because user fee revenue already reflects consumer demand.

[Table 4. Use-related funding mechanisms]

- As with other market mechanisms, vouchers have advantages but also pose risks for sub-central governments. Use-related funding is usually a corollary of user choice but that need not be the case.^19 User choice without the corresponding funding can lead to service degradation (see section on user choice), and user-related funding without user choice leaves providers with few incentives to raise standards (Burger et al., 2006). Finally, voucher systems may become victims of their own success: given that service demand may rise once providers improve service levels, sub-central budget may come under pressure. Use-related funding is hence best applied for services with low price elasticity -- e.g. compulsory education or hospital care -- or where access can be at least partially regulated, e.g. in tertiary education. The advantages and limits of use-related funding mechanisms have been discussed in several OECD publications and for services like education, nursing homes and childcare (Lunsgaard 2002, Joumard et al., 2003, Sutherland and Price, 2007, Erlandsen 2007).

5.3. Results for the intermediate indicator 3 “price signals in funding”

- The extent to which SCGs apply user fees and use-related funding in service provision is measured by institutional indicator 3 “price signals in funding”. This intermediate indicator is based on five low-level indicators (LLIs): LLI-11 measures the percentage of cost covered by user fees, LLI-12 assesses who decides on the level of fees and where the revenues go, LLI-13 is a consistency indicator assessing decision-making processes, LLI-14 measures the extent to which SCGs apply use- related funding (“vouchers”), and LLI-15 measures the share of use-related to total government funding. All information contained in the LLIs is described in the policy parts of this section. Coding for LLIs to obtain the intermediate indicator is shown in Table A1 in the Annex.

- The numerical results for intermediate indicator 3 (Figure 9), show high values for Switzerland, Ireland and the Netherlands and low ones for Italy, Mexico and Portugal. Funding arrangements are particularly consistent in Switzerland and Australia. Averages for ILI 3 are below the averages for ILI 1 and ILI 2, pointing at weak use-related funding. Also, variation across countries is relatively small, suggesting that there is no real vanguard for use- and performance-related funding.

[Figure 9. Intermediate level indicator 3: price signals in funding]

(^19). In some countries hospital funding relies on user-related funding but users have no actual choice among

hospitals

- Primary education : In both figures, primary education covers an intermediate rank across sub-central services. The extent of the policy gap is mainly influenced by low indicator values for use-related funding and the right of private schools to obtain some government funding, while user choice is rather advanced in the countries under scrutiny.

- Secondary education : Secondary education shows almost the same values as primary education. This is not surprising as in most countries the institutional arrangements for both education levels are almost identical. Again the reform potential lies in the funding mechanism, while user choice is quite advanced.

- Tertiary education : Tertiary education has the highest reform potential in the average figure and an intermediate position in the sum indicator. Indicator results show that little reliance on user fees for tertiary education is the single most reason for the high policy reform gap.

- Hospitals : Hospitals cover an intermediate-low position in both figures. Reform potential lies in more user choice and in advanced use-related funding such as diagnosis-related groups. Access to the market for private hospitals is relatively open, although the indicator may underestimate difficulties for private providers to be funded on the same ground as public hospitals.

- Public Transport : Public transport is ranked low in both figures, reflecting a rather strong reliance on market mechanisms. Competitive tendering has become more frequent in local and regional transport, particularly for buses, although all jurisdictions have not yet fully implemented standardised tendering rules. User fees cover a significant part of operating cost.

- Nursing homes : Nursing homes rank relatively high in both figures. The reason is that user choice is often not guaranteed, and if it is, it is usually restricted to the resident’s jurisdiction. Also user fees often cover a small part of total cost only.

- Childcare : Childcare covers a similar position as nursing homes. User choice is a little less restricted, while fees tend to cover a somewhat larger part of total cost.

- Waste collection : Tendering has become common for waste collection in most countries. In some countries there is even free market access for industrial waste collection. Waste disposal, on the other hand, is mostly a public monopoly. 7. Trade-offs and side effects of market mechanisms in public service provision

- Market mechanisms can improve efficiency of public services by introducing competitive forces, by increasing user choice and by relying on more price signals in funding arrangements. However, some trade-offs and side-effects may become apparent when market mechanisms are used more widely. Extending market mechanisms to SCG public services can run counter to the objective of universal public service access, with undesirable distributional effects, both social and geographic in nature. And central government measures to implement market mechanisms at the sub-central level may conflict with local choice, i.e. SCGs’ desire to adapt their arrangements to local circumstances and needs. This last section gives an overview on trade-offs between efficiency and equity and between efficiency and local accountability.

7.1. Equity concerns

- The following paragraphs give an overview of the undesirable effects of market mechanisms may have on equity and the policies sub-central and central government have developed to cope with them.

- User fees : User fees may exclude poorer segments of the population from public services. User fees for hospital or outpatient care may conflict with the principle of universal access. Higher fees for public transport could exclude people from access to transport, particularly those without car. Higher user fees in tertiary education may exclude students from poor families although the efficiency-equity conflict is lower as the current funding rules favour well-off households.

- User choice : User choice itself need not have any distributional consequences but could have adverse effects when combined with more freedom for providers. Providers may be able to screen potential users, thereby filtering social groups with higher-than-average cost. Most funding systems lack the sophistication to deal with such filtering, and some groups may be denied effective access to services such as schools or hospitals.

- Tendering and other forms of contracting out : Tendering itself has little distributional effect. However, depending on the standards imposed on providers with respect to service coverage -- e.g. in public transport -- they may withdraw services for certain social groups or from certain areas. Also, if not regulated properly, service standards may decline after privatisation or tendering of services.

- Governments, both central and sub-central, have policy options to cushion potential adverse effects of increased market mechanisms:

- Setting minimum standards : Central and sub-central governments often set social and/or geographical minimum standards for service providers, including in tenders. Standards may take the form of detailed prescriptions such as a settlement’s right to a school if the number of pupils exceeds a certain threshold, or its right to a certain number of daily bus connections. In some countries, central government requires SCG to provide minimal standards and also co-funds them.

- Providers must accept any user : Countries with user choice generally require providers to accept any potential user. This holds particularly for schools, hospitals and public transport where legal provisions forbid providers to turn users away. Universal access rights are meant to ensure that providers cannot exclude certain social groups, although screening and selection sometimes works through informal channels and is difficult to detect.

- Lower fees for users in need. Most countries set lower user charges and fees for certain social groups. Low-income elderly pay lower fees in nursing homes, the fees for childcare institutions are linked to parent’s income, and public transport companies offer lower fees for students and unemployed. In some cases lower revenues must be borne by the provider, but in most cases the cost of fee reductions based on distributional motives is covered by (central or sub-central) government.

- Direct income support : Means-tested income support is a social policy measure meant to increase the individual or household budget. Government loan guarantees with income- contingent repayment in tertiary education could also be mentioned here. Direct income support enables users to pay for priced public services. Compared to subsidizing a service,